I rented the house I live in sight unseen. The pictures told me enough. Kiva fireplace, Saltillo tile, peeled-log beams, lots of open space. In retrospect I seem to recall that the listing did say something about a mountain, but that didn’t mean anything to me yet.

The mountain turned out to be the mountain, Taos Mountain, and it’s visible from three rooms in the house. In the morning the sun rises from behind the mountain, slowly pouring light on the sagebrush meadow below. When the sun sets on the other side of the Rio Grande, it casts a red glow on the mountain itself. The light show happens twice a day but the mountain has many moods. It can be dark and ominous, looming beneath a silent lightning storm. Then it’s whimsical and flamboyant, conjuring otherworldy halos and rainbows. Sometimes it pulls a cloud curtain down and shuts you out completely.

Taos Mountain has a few names. It’s Pueblo Peak to some, “la Sierra de los Indios” to others, and Skull Mountain to still others, because of a skull shape that appears on its face after a snow. The mountain is sacred to the people of Taos Pueblo. Local lore says if things go well for you here, the mountain allowed it, and if things go pear-shaped, it means the mountain rejected you. People like me can’t climb the mountain, thanks to a 1970 settlement that returned 48,000 acres of holy land back to the pueblo, signed into law by Richard Nixon of all people. So I just look at it a lot, and await its verdict.

One afternoon months into living here, I pulled off the shelf a book I’d owned for years, “Georgia O’Keeffe and New Mexico: A Sense of Place,” and flipped through it with new interest. It’s a monograph from an exhibition of the same name, held in 2004 at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe. This time, the paintings were more than works of art, more than images of objects in a museum. The landscape they depicted was alive to me. I recognized the wide, green river as the Chama. I knew by the color palette which hills were closer to Abiquiú, where the land is more pink.

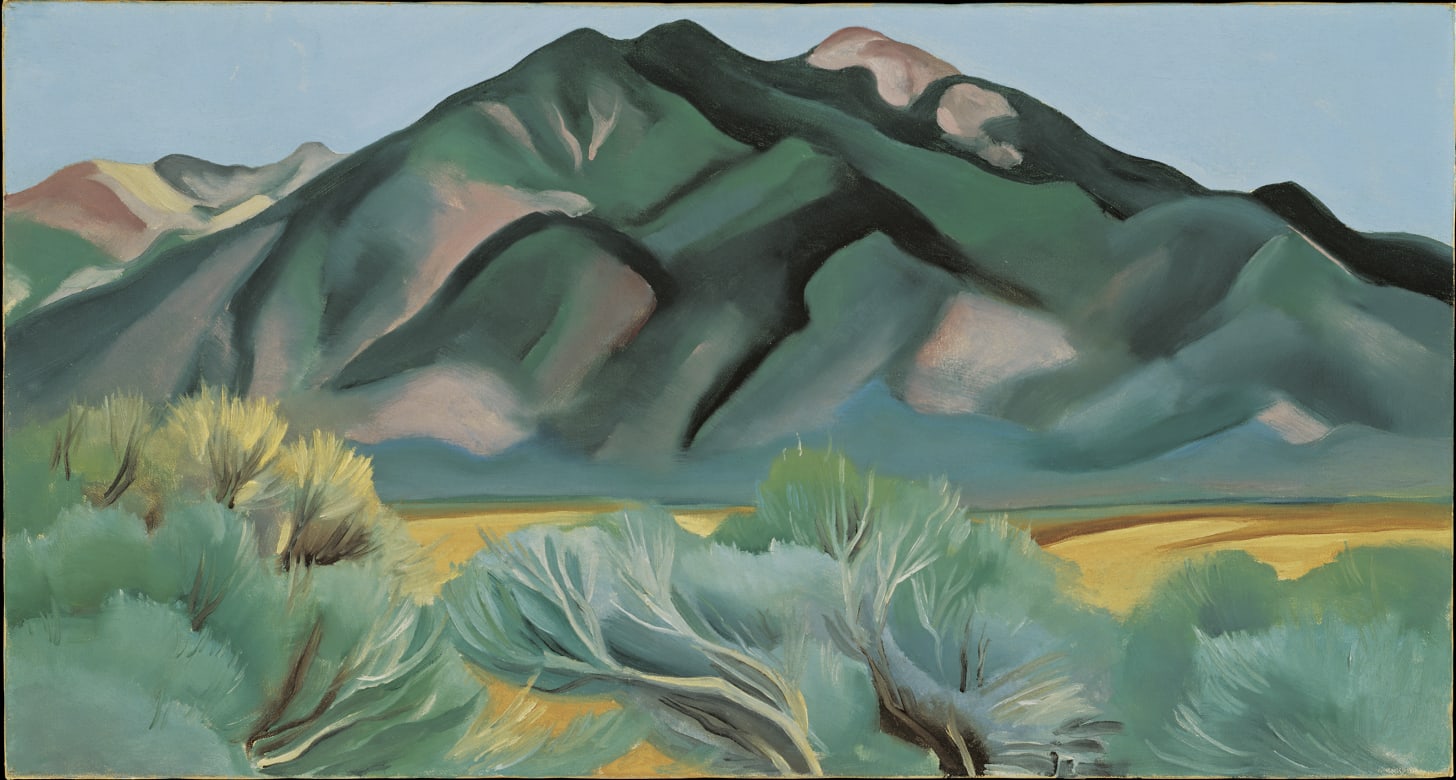

Page sixty-five stopped me in my tracks—the two peaks, one slightly higher than the other, with the familiar series of ridges below. I didn’t need to read the caption to know it was the mountain I can see from my bedroom window.

O’Keeffe painted it in 1930, it turns out, during her second summer in New Mexico. She spent most of the first two summers in Taos. The writer-impresario Mabel Dodge Luhan had invited O’Keeffe to live and paint in a studio at Los Gallos, her adobe home, salon and artist colony near town. (Other guests at “Mabeltown” over the years: Mary Austin, Willa Cather, D.H. Lawrence, Aldous Huxley, Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Martha Graham and Carl Jung.) O’Keeffe’s studio had a direct view of the mountain.

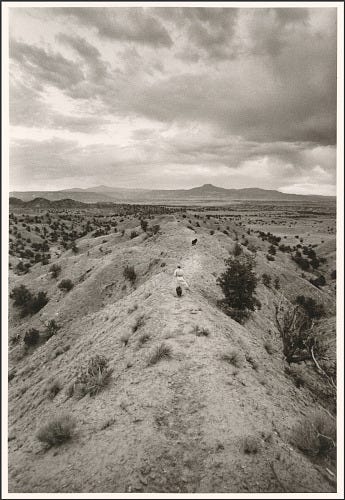

She mentioned the mountain in her earliest letters home to Alfred Stieglitz. “The window facing north toward the Holy Mountain is so big,” she wrote. On this day in 1929, O’Keeffe had gone out walking way up into the hills. She had never been on such a beautiful walk. The meadows covered in sagebrush looked like the ocean. “I seem to be hunting for something of myself out there,” she wrote, “something in myself that will give me a symbol for all this—a symbol for the sense of life I get out here.”

The mountain acquired a heavier presence over time. She admired it from the pueblo: “I had a really beautiful afternoon—the simple Pueblo village—all of mud—against as perfect a mountain as one could imagine.” She observed its disappearing act from Los Gallos: “In the studio again—have watched a storm hide the mountain—and watched the mountain come again.” In a letter to a friend after the second summer, she described its pull: “The Mountain calls one, and the desert—and the sagebrush—the country seems to call one in a way that one has to answer it.”

It was from Taos that O’Keeffe began to wander into more remote areas, to go further out. She learned to drive so she could go where she wanted. In Alcalde she painted a black mesa landscape. In Tierra Azul she painted three gray hills. She found Abiquiú in 1931, Ghost Ranch a few years later. The outside world came to know this region as O’Keeffe Country, a term that has since fallen out of favor. She called it “the faraway.”

O’Keeffe went on to paint other mountains with more devotion. She painted Pedernal, the square-topped mountain near Abiquiú, some two dozen times because, she often said, “God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it.” But I like knowing she started here, with this mountain. I think she got its blessing.

This is great Abby

A wonderful moment - when you turn the page and immediately know the mountain - a touchpoint with the great artist